Optimal Risk-Adjusted Return

Multi-dimensional diversification can optimize the tradeoff between risk and return

To invest is to take risk. In efficient markets, taking greater risk is generally expected to deliver higher return. The dual objectives of most investors is to maximize return while minimizing risk, in other words, to achieve an optimal “risk-adjusted return.”

First, an investor and/or their advisor must set the level of risk the investor is comfortable taking. Then, they build a portfolio designed to maximize the expected return for that level of expected risk. Higher diversification generally dampens the volatility of the portfolio and therefore increases the risk-adjusted return.

First, an investor and/or their advisor must set the level of risk the investor is comfortable taking. Then, they build a portfolio designed to maximize the expected return for that level of expected risk. Higher diversification generally dampens the volatility of the portfolio and therefore increases the risk-adjusted return.

The importance of full diversification has been recognized over many decades by Nobel laureates such as Harry Markowitz, Wiliam Sharpe and Eugene Fama, as well as by innumerable academic and commercial research studies.

Diversification can be achieved along many dimensions including asset class, sector and other factors outlined below. However, there is another very significant dimension of diversification: time. Markets themselves are highly volatile but long time horizons tend to smooth out the market returns. Not only do unadvised clients tend to underutilize traditional diversification, they typically underutilize the benefits of time-based diversification as well.

Diversification can be achieved along many dimensions including asset class, sector and other factors outlined below. However, there is another very significant dimension of diversification: time. Markets themselves are highly volatile but long time horizons tend to smooth out the market returns. Not only do unadvised clients tend to underutilize traditional diversification, they typically underutilize the benefits of time-based diversification as well.

Unadvised investors are often hampered by their emotions – they assume the immediate future will be like the immediate past. Over-enthusiasm in good times and hesitant caution in bad times often leads them to buy high and sell low. Some of the reasons are loss aversion, recency bias and herd mentality.

Diversification is widely considered the most reliable way to increase your risk-adjusted return.

Diversification is widely considered the most reliable way to increase your risk-adjusted return.

RISK & RETURN

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

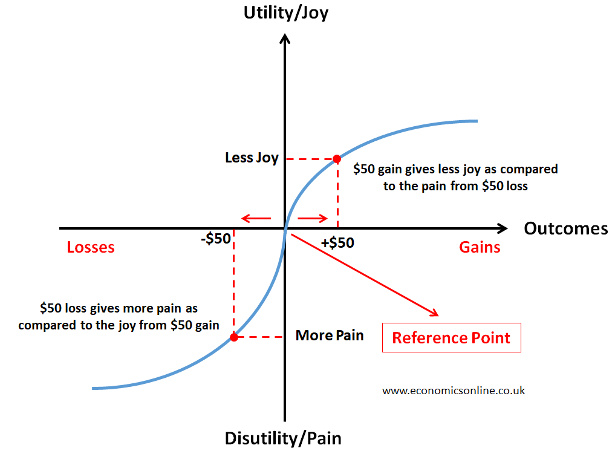

The initial insight that begat behavioral finance was Prospect Theory. Three Nobel laureates had a hand in its development. Originally proposed by Daniel Kahneman, it was later tested and elaborated by Richard Thaler.

Prospect Theory is about risk-aversion. Most people experience losses as more painful than similar gains are joyful. Interestingly, those feelings are not related to how much someone has, but rather to how much they gain or lose.

Prospect Theory is about risk-aversion. Most people experience losses as more painful than similar gains are joyful. Interestingly, those feelings are not related to how much someone has, but rather to how much they gain or lose.

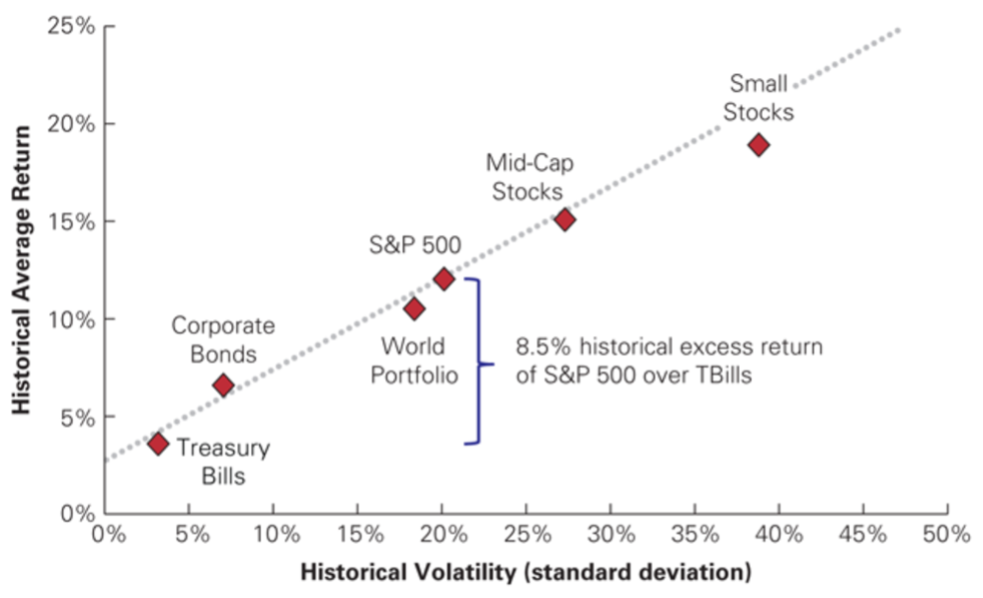

In the absence of a compelling reward, a risk-averse investor would put their money in Treasury bills, which are referred to as “risk-free” assets. The greater the anticipated risk of a potential investment, the greater the expected return must be to justify making that investment.

The relationship between risk and return was first codified by another Nobel laureate, William Sharpe, who proposed the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). CAPM attempts to quantify the relationship between risk and return. It states that investments with greater risk, often referred to as volatility, require higher expected returns to entice investors to invest.

The relationship between risk and return was first codified by another Nobel laureate, William Sharpe, who proposed the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). CAPM attempts to quantify the relationship between risk and return. It states that investments with greater risk, often referred to as volatility, require higher expected returns to entice investors to invest.

Over the years, there have been numerous academic critiques of the CAPM, but most observers agree that the relationship between risk and return is conceptually sound.

DIVERSIFICATION

Maximize your risk-adjusted return

Diversification can reduce volatility (the variability of the return) and therefore reduce risk. As you add additional asset classes or securities, the volatility of the portfolio as a whole is reduced versus the average volatility of the individual securities.

This is true as long as the securities are not perfectly correlated. As an unrealistic but simple illustration, if two stocks always go up and down at the same time (they are perfectly correlated), the two stocks individually will have the same volatility as the two stocks combined. However, if one goes down when the other goes up and vice versa (they are perfectly uncorrelated), by combining the two stocks together, the volatility would be zero.

Most investment securities are somewhat but not perfectly correlated. So, combining multiple securities of different types will lower the volatility of the portfolio. A portfolio can be diversified along multiple dimensions.

This is true as long as the securities are not perfectly correlated. As an unrealistic but simple illustration, if two stocks always go up and down at the same time (they are perfectly correlated), the two stocks individually will have the same volatility as the two stocks combined. However, if one goes down when the other goes up and vice versa (they are perfectly uncorrelated), by combining the two stocks together, the volatility would be zero.

Most investment securities are somewhat but not perfectly correlated. So, combining multiple securities of different types will lower the volatility of the portfolio. A portfolio can be diversified along multiple dimensions.

- Asset class – stocks, bonds and cash

- Asset group – Magnificent Seven vs the rest of the S&P 500

- Sector – information technology, healthcare, etc.

- Size – mega, large, mid and small market capitalization

- Style – growth, blend and value, or momentum

- Dividend – high, low and no dividend

- Fundamentals – growth, price / earnings, etcetera

- Geography – domestic vs non-U.S. developed vs emerging markets

- Currency – fiat denomination or, arguably, cryptocurrency

The most common and valuable form of diversification is asset allocation, expressed as the proportion of stocks, bonds and cash. A combination of other dimensions, also known as factor-based diversification, can further reduce volatility. The more assets of different types in a portfolio, the lower the overall volatility.

A broad index like the S&P 500 has lower volatility than ten stocks chosen randomly from the S&P 500. There is no reason to assume that, on average, the random group will perform better or worse than the index. So, the group of ten stocks will have the same expected return as the index but higher volatility. This is called “uncompensated risk”, meaning you are taking more risk than necessary for that level of return.

Investors seek the lowest risk for a given level of return, or the highest return for a given level of risk. This is measured as the “risk-adjusted return”. Multi-dimensional diversification can increase your risk-adjusted return.

A broad index like the S&P 500 has lower volatility than ten stocks chosen randomly from the S&P 500. There is no reason to assume that, on average, the random group will perform better or worse than the index. So, the group of ten stocks will have the same expected return as the index but higher volatility. This is called “uncompensated risk”, meaning you are taking more risk than necessary for that level of return.

Investors seek the lowest risk for a given level of return, or the highest return for a given level of risk. This is measured as the “risk-adjusted return”. Multi-dimensional diversification can increase your risk-adjusted return.

LONG-TERM INVESTING

Time is your friend

There are three benefits to long-term investing: time-based diversification, compound returns and behavioral discipline.

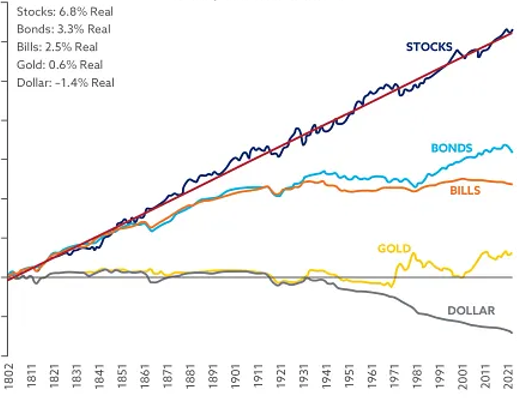

Time is a separate and sometimes overlooked dimension of diversification. The equity and fixed income markets have their own volatility – they could be up 10% one year and down 10% the next. Those fluctuations are smoothed out over time. For example, even including the Great Depression, the average returns on stocks, bonds and other asset classes have been relatively consistent since the early 1800s.

Time is a separate and sometimes overlooked dimension of diversification. The equity and fixed income markets have their own volatility – they could be up 10% one year and down 10% the next. Those fluctuations are smoothed out over time. For example, even including the Great Depression, the average returns on stocks, bonds and other asset classes have been relatively consistent since the early 1800s.

The second advantage of long-term investing is compounding. In a bank account, compounding means you earn interest on your interest. The same is true of investment returns. The cumulative balance of a 10% return compounded over 25 years is three times as large as it would be without compounding.

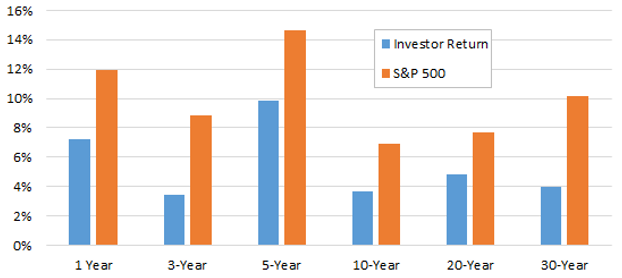

The third advantage of long-term investing is behavioral discipline. By committing to a consistent investment policy and sticking to it over multiple market cycles, the average return for many investors can be increased. A long-running study by DALBAR has consistently shown that individual investors who buy ETFs and mutual funds perform worse than the funds themselves.

The third advantage of long-term investing is behavioral discipline. By committing to a consistent investment policy and sticking to it over multiple market cycles, the average return for many investors can be increased. A long-running study by DALBAR has consistently shown that individual investors who buy ETFs and mutual funds perform worse than the funds themselves.

Richard Thaler and others have identified some of the reasons for this persistent performance gap. “Recency bias” leads people to think that whatever has been happening in the immediate past, such as stocks going up, will continue to happen in the immediate future. “Herd mentality” leads investors to go along with the crowd when other investors are optimistic and when they are pessimistic. Both can lead investors to buy high and sell low, thus reducing their returns.

A long-term approach to investing which maintains the same investment behavior over many years can help yield a better cumulative compound return on your funds.

Diversification in all its forms can increase an investor’s risk-adjusted return and help build lasting wealth for you and your family.

This content is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice, a recommendation, or an offer to buy or sell any securities. All investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Diversification and long-term investing do not guarantee a profit or ensure against loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

A long-term approach to investing which maintains the same investment behavior over many years can help yield a better cumulative compound return on your funds.

Diversification in all its forms can increase an investor’s risk-adjusted return and help build lasting wealth for you and your family.

This content is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice, a recommendation, or an offer to buy or sell any securities. All investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Diversification and long-term investing do not guarantee a profit or ensure against loss. Past performance is not indicative of future results.